How to keep a notebook

Ideas from Boswell, Botsford, Chatwin, Highsmith, Pepys, Sebald, Sedaris, and Woolf

Over the years, we have discussed a lot of advice about how to keep a notebook.

In preparation for a discussion of Joan Didion’s “On Keeping a Notebook” and inspired by a comment from John Dickerson in a recent Political Gabfest episode, here are some assembled thoughts about how other writers kept their notebooks.

From the passages below, one can create a list of "best practices." Neither of us follows all of these rules and there are other notetakers and diarists who avoid these practices brilliantly. Nonetheless:

Carry a notebook with you at all times and write down your note as soon as it occurs to you.

Focus on others more than yourself.

Capture what people say.

Avoid feelings.

Type up your notes and create an index.

Keeping a notebook is a topic that I, Adam, have considered since—checks calendar—exactly 20 years ago. I was working for my former professor, Keith Botsford, and part of the job was listening at length to him tell me how I should do things:

19 Jan 2002

KB told me he wanted me to read some “real” journals so that I would know how to keep a serious journal. He mentioned that the best is André Gide's but I won’t be able to read it until it's published in English next year.

22 Jan 2002

KB says to "normalize" my journal by typing it up regularly and indexing it.

12 Feb 2002

Talked with KB today about journaling “the right way.” He says to “be as little self-concerned as possible, record what everyone else says, not what you say." Write about things as they happen don’t bother wrapping up the whole day. Type up the journal and index it. Read the journals of Pepys and Aubrey’s Brief Lives. Finally he told me to think about things physically as well as mentally. For example, I should note that KB had his legs propped up on his desk. He said that if I learn to journal properly I’ll be three decades ahead of him.

Samuel Pepys used shorthand to write about everyday life and major events.

From "And so to bed – a goodbye to Pepys’s diary" by Deborah Swift:

Pepys’s daily entries combine coverage of major crises, such as the Plague and the Great Fire of London, with political events, gossip, and intimate details of his many affairs. It holds nothing back and tells us what people ate, how they relaxed – Pepys was a great musician and theatre-goer – how they spent their money, and all the details of the minutiae of everyday life. Reading Pepys is like looking over his shoulder as he writes; you can almost smell the tallow from his candle.

Pepys began his entries on New Year’s Day in 1660 using Thomas Shelton’s shorthand, a method he probably used in his work life for speed. He wrote with a quill pen in standard notebooks of 282 pages, with hand-ruled margins in red ink. The diary at first looks like impenetrable code – all squiggles and dots with only the occasional recognisable word. Pepys also used this ‘code’ for privacy; for he certainly would not have wanted his wife to read about his extra-marital affairs, or the King to hear his frank opinions of life at court, though for 21st-century readers these are the parts that make his diary so vivid.

James Boswell wrote down notes immediately.

From James Boswell Finds His Voice by Leo Damrosch:

Of crucial importance was the commitment to veracity that Boswell said his father had thrashed into him. All his life he wrote down notes, if not full narratives, as soon after an event as possible. Otherwise, “one may gradually recede from the fact till all is fiction.” A modern critic has coined a term for the result: “the fact imagined.” In an early journal Boswell found an apt metaphor for the telling details he wanted to preserve: “In description we omit insensibly many little touches which give life to objects. With how small a speck does a painter give life to an eye!”

David Sedaris avoids feelings and makes something like an index.

David Sedaris keeps a notebook in his shirt pocket. "In it I register all the little things that strike me, not in great detail but just quickly." We have more about how his stories move out of his notebook in this blog post.

For a few weeks I've had in my head that he suggested writing about things that actually happen, not how you feel about them. I think I inferred that from this recent interview in the NYT Book Review Podcast:

Sedaris: I don’t write about my feelings, so I didn’t have that to be embarrassed about. [...]

I’m not that interested in my feelings. And I’m not interested in anybody’s feelings, really. When somebody uses that word in a sentence: “Well, I’ve been feeling really —” like, “I’ve been feeling really exterior lately,” or “I’ve been feeling really vulnerable,” I don’t care. I like to hear a story. I just turn off when people talk about their feelings.

I mean if somebody says they’re angry at me, I don’t mean that I turn off there. I listen to that. But just that sort of wishy-washyness of feelings.

Pamela Paul: I guess most people’s diaries are probably 98% feelings. And maybe that’s what makes them largely unreadable to people other than the diarist.

David Sedaris:

I think the word diary connotes feelings. I don’t think the word journal connotes feelings so much as diary, but I wouldn’t say that I keep a journal. I would say that I keep a diary.

Sedaris talks about something like indexing in 2018 (also in the NYT Book Review Podcast):

I think I've read through all of my diaries twice. Because I have a guide on my computer. A lot of what's in there is not of interest to anybody. But if something is of interest then I'll put it down on my guide and that helps me if I'm working on a story or an essay. I can go back through it. If I were to write an essay about all the haircuts I've ever had, then I can just type haircut in there. My hair's not special in any way. All that's special is that encounter. That's going to come in handy someday.

Virginia Woolf, like many diarists, filled her notebooks with character sketches.

Rosemary Dinnage in her review of the fifth volume of Woolf's diaries:

Character sketches of great panache abound again: Maugham—“A look of suffering & malignity & meanness & suspicion. A mechanical voice as if he had to raise a lever at each word—stiffens talk into something hard cut measured”; Beatrice Webb, “as alive as a leaf on an autumn bonfire: burning, skeletonised”; a long, ineffably amused piece on the elderly H.G. Wells. Also one curious vignette: the Woolfs meet the aged Freud in his Hampstead refuge, he hands her a narcissus (presumably no significance intended?). Of course it would be foolish to say that in years of private diarizing there is no dross: who met whom and who was at the party may have to be skimmed over. And sometimes the speed of associations runs so fast that it almost leaves the reader behind, with a sense of incoherence. But nearly always the diary does solve it—“the old problem: how to keep the flight of the mind, yet be exact.” One of its main functions surely was to limber up on that crucial aesthetic preoccupation.

Bruce Chatwin found a place for everything in his notebooks.

Elizabeth Chatwin, paraphrased:

Everything went into Bruce Chatwin’s notebooks: observations, anecdotes, recipes, addresses, the names of trees…. He made small sketches, almost like etchings. He remembered what was in his notebooks quite well. He was said to have noted the tragedy of losing such a notebook, that losing a passport was an inconvenience but losing a notebook was a tragedy.

This acknowledgement of the fallibility of memory is honest and heartbreaking.

WG Sebald encouraged theft.

The Collected 'Maxims' of WG Sebald recorded by David Lambert and Robert McGill

I can only encourage you to steal as much as you can. No one will ever notice. You should keep a notebook of tidbits, but don’t write down the attributions, and then after a couple of years you can come back to the notebook and treat the stuff as your own without guilt.

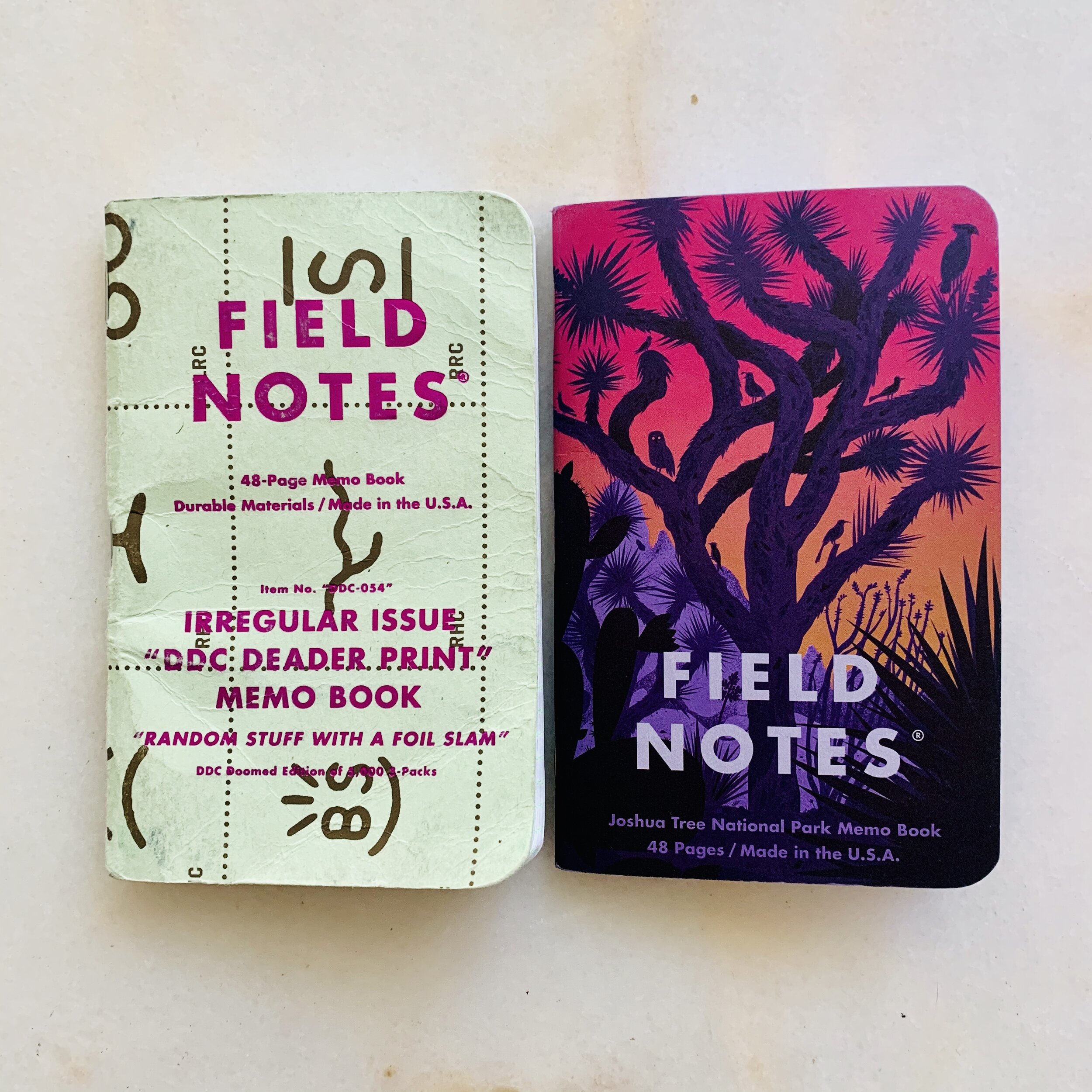

When all else fails, buy more pens and notebooks.

At times, I try to make a practice of switching between black and blue ink, for notetaking and fiction writing respectively. Patricia Highsmith kept two journals for the two parts of her mind. I've shared more on the notebook habits of Patricia Highsmith, John le Carré, architect Jun Aoki, and journalist Jenny Kleeman here.